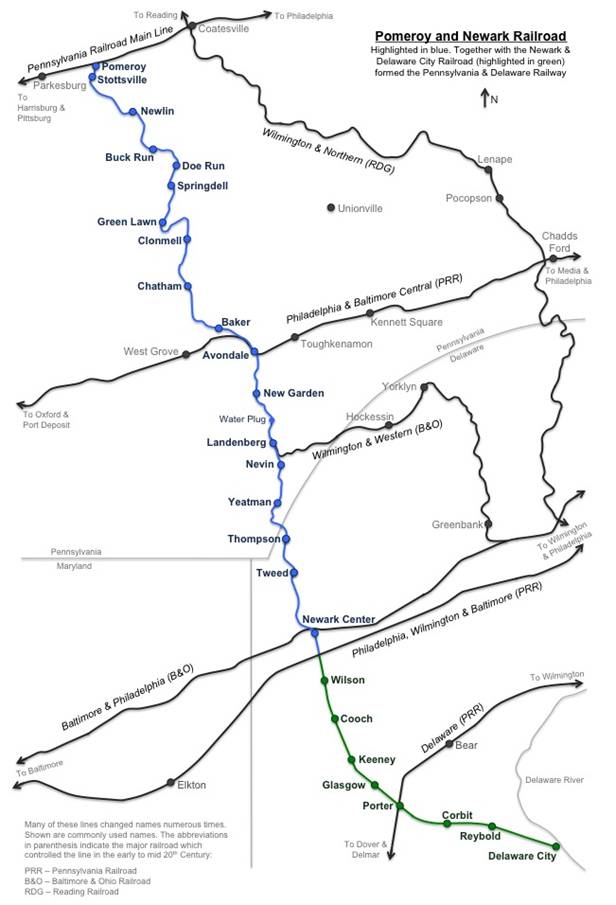

The Pomeroy and Newark Railroad

Revised September 2010

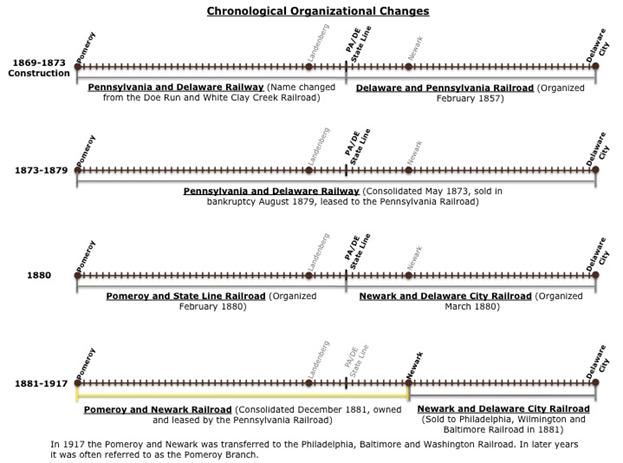

Dates of Construction: 1869-1873

Dates of Abandonment in New Garden Township: 1936 South of Landenberg, 1943 North of Landenberg

Length in New Garden Township: 1.8 miles

Stations in New Garden Township: Landenberg

The Pomeroy and Newark Railroad was without doubt the least successful of the three train lines that wound through New Garden Township. Construction occurred during the second half of the 19th Century, the boom period of the railroad industry, when trains captivated the nation. No terrain seemed insurmountable and every small route appeared to possess great potential. Many of the speculative local lines built during this era promptly failed, swallowing the invested savings of thousands of farmers and businessmen. The Pomeroy and Newark never approached initial investors’ expectations and their losses were particularly high.

The original stakeholders built the line stretching from Pomeroy, Pennsylvania to Delaware City, Delaware to provide the Pennsylvania Railroad access to an ice free port on the Delaware River. The powerful Pennsylvania Railroad suffered from insufficient terminal facilities at the end of its Main Line in Philadelphia and sought another outlet for the growing freight traffic pouring in from new routes in western Pennsylvania and Ohio. Although Delaware City was no more than a quiet town, railroad officials considered it a viable option for a port; it was mostly downgrade from the Main Line at Pomeroy allowing gravity to facilitate the passage of long coal trains, and far enough south to avoid the winter ice in the Delaware River (pollution and warmer temperatures had yet to prevent ice from sealing the port of Philadelphia). Furthermore, Delaware City’s location closer to the mouth of the river reduced the total mileage freight had to travel from the west to reach the Atlantic. Shortening this distance promised to make the Pennsylvania Railroad more competitive with its rival, the New York Central, which enjoyed well established port facilities on the Hudson River. The small line did not go unnoticed by these competitive interests. A New York Times editorial in April 1873 cautioned readers about the potential threat from this new route:

The communication between the navigable waters of the Delaware and the great West is becoming every day more and more intimate, and the foreign trade which at present appears to be so rapidly growing up on that river, small as it still is compared with that of this port, is a thing which should at least suggest to us the question whether we are not in danger of indulging a degree of confidence in our own position, which may in the end prove far from beneficial to our commercial prosperity.[i]

Recognizing the speculative nature of the venture, the Pennsylvania Railroad encouraged local supporters to subscribe to stock in the line and attempted to limit its contribution primarily to political support and construction assistance. This typified the giant railroad’s strategy in this time period. It leased and operated a line after others invested significant capital, leaving open the possibility to purchase and control the track for pennies on the dollar if the project failed.

Significant lobbying was required to raise the funds needed for construction. An article written for the West Chester Jeffersonian newspaper blasted those who refused to contribute or stood in the railroad’s path:

Many who now think this road will be of no service to them, will, in future years, when advertising their farms for sale, give prominence to the fact that they are near a station on the [railroad], well knowing that no purchaser of land will go far from a R.R. and buy unless at a very low rate.[ii]

It continued by emphasizing the prospects for the line:

The route is surrounded by almost every element of strength to make a successful and profitable road, either for freight or passengers, a dense population, a rich agricultural region, numerous factories and villages, bodies of iron ore, and a limestone district on the borders of the Delaware, nearer to the peninsula than any other.[iii]

As the article indicates, the railroad had the potential to serve numerous local purposes as well as the Pennsylvania Railroad’s strategic interest. Most residents were thrilled about the prospect of this new form of transportation reaching their doorsteps. Communities were thriving up and down the Buck Run, Doe Run and White Clay Creek Valleys, and farmers and merchants looked to the railroad as a way to expand their markets. The initial excitement and lobbying generated enough capital contributions to complete surveys and begin grading the line in 1869. A few large contributors helped propel stock subscriptions for the portion of the line in Pennsylvania. One prominent initial investor was Martin Landenberger, the entrepreneur who consolidated and expanded the woolen mills in Landenberg. He served as an early director and reportedly contributed close to half a million dollars to the construction of the line, an enormous sum in the early 1870’s.[iv] The railroad permitted the cheap and efficient movement of raw materials to the Landenberg mills and the delivery of yarn to the company’s stocking mills in Philadelphia. As a director, Landenberger pleaded and fought with the Pennsylvania Railroad for financial contributions to the point of his resignation in 1872.[v] Ultimately, the valleys’ farmers and entrepreneurs could not cover the construction cost alone and the Pennsylvania Railroad periodically injected small amounts of capital to sustain the project.

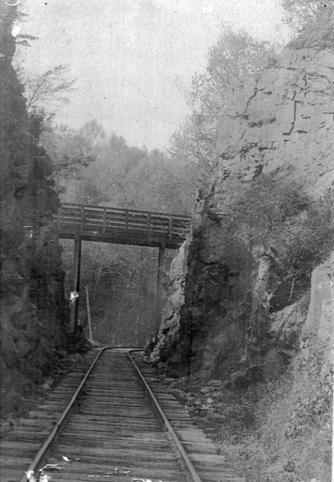

The steep topography of the local valleys complicated the planning and construction of the railroad. The portion of the line in the southwest corner of New Garden Township was one of the most challenging sections. In order to thread the track into Landenberg from the north, engineers built five large bridges over the White Clay Creek and blasted a 300 ft long, 50 ft deep cut through the hillside all in less than a mile. North of Auburn Road, construction crews permanently altered the course of the White Clay to avoid building two additional crossings. Other than rudimentary dynamite, limited tools existed to help construct the rail bed. Many local farmers pitched in with their teams of horses to assist with the grading. Two teams and one man received $4.50 a day for their assistance.[vi] Hundreds of laborers, many of them recent immigrants, were recruited to supply additional manpower. Families along the route provided support for the workers. John and Lydia Miller, who lived off Garden Station Road in the extreme southeastern corner of London Grove Township provided accommodations for many of those engaged in constructing the track between Avondale and Landenberg.[vii] Despite the support, the working conditions were difficult, particularly during the winter. Workers struggled to keep warm grading the line amid the chilly winds, snow and icy streams. A local paper reported in March of 1872, “complaint has been made by farmers that the workmen during the cold weather made free use of their fences for fuel. Fence rails being dry burn better than cord-wood.”[viii]

Bridge #44, one of the five bridges over the White Clay Creek north of Landenberg (2009)

Large cut north of Landenberg circa 1910. Penn Green Road crossed the railroad on the bridge in the background. (New Garden Historical Commission files)

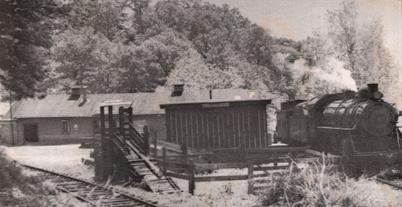

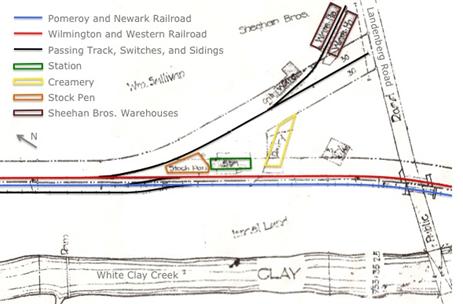

After over two million dollars of investment and nearly four years of construction fraught with delays, the first regularly scheduled passenger train steamed down the track with much fanfare on June 30, 1873. The Daily Local News reported, “The people are wild with enthusiasm over the event of the opening of this new thoroughfare of enterprise through their localities.”[ix] The original line, known as the Pennsylvania and Delaware Railway, opened with 17 stations (more were added). Many of the stations were named for the initial supporters’ farms and villages through which it passed. Trains stopped at Baker Station north of Avondale where Baker & Phillips quarried limestone; Aaron Baker had been one of the early proponents and directors of the line. Many of the original bridge abutments were built from stone quarried on his property.[x] Landenberg was the only official stop in New Garden Township. The railroad shared the station building with the Wilmington and Western Railroad, which arrived from Hockessin in the Fall of 1872. A passage in the local newspaper described the initial station, which opened in 1873, as “not strictly of the Grecian nor yet Roman order of architecture, but embraces much that is useful and beautiful from both.”[xi] Apparently it failed to embrace much of either as only two years later the railroads built a “new and handsome” station to replace the “old shed.”[xii] An additional track was added in Landenberg in 1876 to help facilitate the transfer of shipments between the railroads. A siding branched off to the north of the line and ran both into and parallel to the lumber and coal yard later owned by the Sheehan family. Customers pulled their wagons, and later trucks, up to the siding to receive loads of coal.

Train at Landenberg Station in 1941 (looking southeast). This is the side of the station building. The fencing in the foreground forms a small cattle pen. The building in the background is the creamery. The track in the front left of the photo runs to Sheehan's yard (see photo and map below). (New Garden Historical Commission files)

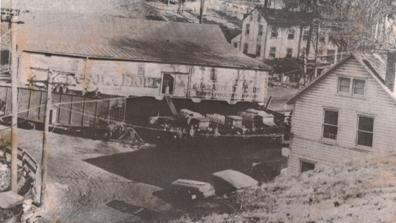

Sheehan Brothers Warehouse. Sheehan ran a coal and lumber yard and sold farm supplies. (New Garden Historical Commission files)

Bridge carrying the tracks over Landenberg Road. The steel road bridge in the foreground stood until the Fall of 2009. It reopened in the Summer of 2010 with many of the original features preserved. (New Garden Historical Commission files)

Landenberg Valuation Map (adapted from a Wilmington and Western blueprint). (New Garden Historical Commission files)

A mile up the line, across the bridges and through the cut, engineers built a dam on the small stream that winds west from the end of Laurel Heights Road. Water flowed through a small pipe from the dam to a water plug adjacent to the tracks. The water plug stood roughly eight feet tall and had an arm that could be swung over the tender. It served as a spigot for train crews to refill their steam engines approximately halfway along the line. There was also a siding used for public delivery on the east side of the main line where local farmers could receive and ship materials, with a small access lane off of Auburn Road. The stop was often referred to as “Water Plug Siding,” owing to the water source. Pennsylvania Railroad manuals from the 1890’s also list the stop as “The Graham Kaolin Co.,” one of the primary kaolin mining businesses in the township. Although the company shipped most of its clay east on the Wilmington and Western, which ran closer to the kaolin mines, this siding may have been used to receive materials or provide an alternative shipping point.

Remnants of the dam near the Water Plug Siding (2009)

The next official station on the line north of Landenberg was New Garden, located a few hundred meters into London Grove Township on Garden Station Road. The station and a gristmill stood just north of the road on the east side of the main track. No known photographs or drawings of the station exist and its appearance is unclear. Martin W. Meloney, who lived on a farm nearby, donated $100 for its construction, a sufficient amount at the time to build at least a small wooden structure.[xiii]

Approximate location of New Garden Station (looking north from Garden Station Road) (2009)

Financial difficulty afflicted the railroad from the start. The winding nature of the line made operating long coal trains difficult; the curves stressed both the rails and the cars. Furthermore, large port facilities failed to materialize at Delaware City. Revenue from the local stores and industries fell far short of covering operating expenses. The numerous wooden bridges and grading required frequent maintenance, which compounded the problems. Trees and ice chucks lodged behind the timber bridge supports during floods, often exerting enough pressure to dislodge the structures from their foundations. In addition, the Board of Directors acquired $1,083,000 of first mortgage debt and $519,000 of second mortgage debt, both of which bore an interest rate of 7%. These required payments of over $112,000 each year. Even at its peak after the turn of the century this small line usually earned less than half of this in revenue, let alone profit. In addition to these mortgages, the railroad carried a small amount of floating debt. Needless to say, the stockholders’ $900,000 interest looked all but lost. The Pennsylvania Railroad elected not to renew its lease in February 1879. This was likely the final straw, and the railroad, faced with insurmountable losses and the inability to satisfy creditors, declared bankruptcy later that year, after only six years of operations.

Mr. Dell Noblit, President of the Corn Exchange Bank in Philadelphia, who was affiliated with the Pennsylvania Railroad, purchased the line for a meager $100,000 at public auction in August 1879, indicating the bleak prospects for the enterprise. Initial investors, including Landenberger, lost everything. Realizing that large port facilities were not materializing at Delaware City, the Pennsylvania Railroad considered leasing and using the Wilmington and Western line out of Landenberg to establish the warmer water port facilities at Wilmington. During this brief time the Wilmington and Western was successfully operating trains between Wilmington, Landenberg and Pomeroy. It was reported that the trains were often long enough to require two engines.[xiv] The prospects seemed high for a joint venture. However, the Pennsylvania’s strategy fizzled as speculators and later the Baltimore and Ohio gained control of the Wilmington and Western to capitalize on its valuable trackage rights into Wilmington. The Pennsylvania Railroad reluctantly assumed control of and leased the portion of the Pennsylvania and Delaware line between Pomeroy and Newark, renaming it the Pomeroy and Newark Railroad in December 1881. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, also controlled at this time by the Pennsylvania Railroad, acquired the line between Newark and Delaware City. With the original route divided at Newark, the Pennsylvania’s dreams of using the line as a shortcut to a significant new port on the Delaware River effectively vanished. Fortunately, a much flatter and straighter route running along the Susquehanna River from Columbia to Perryville opened in 1877 and largely satisfied the need for such a line. The Pomeroy and Newark became primarily a local railroad.

Local traffic remained insufficient to cover operating expenses and the line ran at a loss even in good years. The corporate ledger lists deficits in every year from 1881 to 1911. What revenue the line did earn came primarily from freight service. In addition to agricultural products, the Buck Run and Doe Run Valleys had numerous paper, saw and flour mills. E.A. and J.L. Pennock ran a successful lumber business in Chatham. Further south, the lime and stone quarries near Baker Station provided additional freight. Train crews also unloaded significant quantities of beer at Baker in the mid-1890’s, prompting a correspondent for the Daily Local News to ponder whether it was a speakeasy:

The amount of beer unloaded every two or three days at Baker Station… is a source of wonder to beholders. On Saturday afternoon last the supply shipped to that point consisted of ten kegs, containing not less than fifty gallons, beside six cases of two dozen bottles each of this intoxicating beverage. A train official told a passenger that this was no unusual shipment and the matter is a general topic of discussion among travelers…[xv]

Most of the business in New Garden Township came from Landenberg. In addition to the woolen mills and Sheehan’s coal and lumber business, a bone mill on the southern edge of town, just south of the New Garden Township line, received shipments of buffalo bones from the Great Plains to grind into fertilizer. Most of the industry south of Landenberg was concentrated on the northern side of Newark. A lumber business, the Atlantic Refining Company, and later the American Vulcanized Fibre Company provided traffic for the route. In the early days before the bankruptcy, the portion of the line near Delaware City handled peaches bound for markets to the north and west. According to Amos Osmond, the longtime conductor on the Pomeroy and Newark, the railroad also hauled munitions and other sensitive materials under the watchful eyes of soldiers during the First World War.[xvi]

The Bone Mill south of Landenberg. The siding running next to the top story facilitated the loading and unloading of materials. (New Garden Historical Commission files)

The railroad carried smaller shipments of goods for the local stores, which residents depended on for their everyday needs. A wreck in 1887 one and half miles below Landenberg exposed one transported commodity. The local newspaper correspondent on the scene reported, “One car was partly loaded with watermelons. The younger part of the spectators seemed to know it, as your correspondent saw some watermelons take legs after dark, walk up the bank and disappear into a corn field beyond. Some few rushed down the railroad and disappeared in the darkness.”[xvii] Milk traffic was another significant source of business for the line. Chester County had numerous dairies, and farmers used the railroad to ship their raw milk to creameries. An icehouse on the northern portion of the route above Clonmell station provided crews with a source of ice to keep the milk cool during transit. Milk cans were a common sight on station platforms as farmers would often leave the full vessels for freight handlers to load and return empty later in the day.

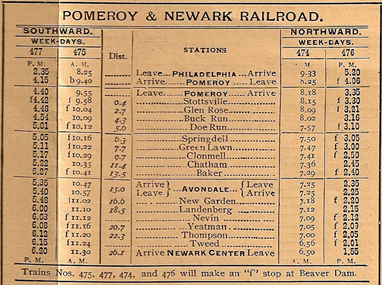

Receipts from passenger service were small, averaging slightly over $5,000 a year between 1881 and 1893. A ticket in 1907 cost three cents per mile in Delaware and two cents per mile in Pennsylvania.[xviii] The entire journey from Pomeroy to Newark cost slightly over 50 cents. Passenger trains ran twice a day in each direction on weekdays, departing Newark around 7am and 2pm and Pomeroy around 10am and 5pm. In the 19th Century the passenger cars were coupled to the freight trains, which precipitated notorious delays. After only two months of operations the Daily Local News reported, “A joker says that the passenger trains… from Pomeroy to Delaware City, run tri-weekly, meaning that it takes them one week to go up and two weeks to come down.”[xix] Beginning in 1901, the Pennsylvania Railroad began operating passenger only trains on the line. A steam engine pulled a passenger coach and a combination car for carrying baggage and picking up and dropping off milk cans along the route. Amos Osborne’s two sons worked along side him as the baggagemaster and fireman, prompting the local paper to joke, “Conductor Osborne is sorry that he ran out of sons before the train was fully equipped.”[xx] A mail handler also frequently worked on the passenger trains, picking up, sorting and delivering mail to the stations. The mail contract generated approximately $800 a year in additional revenue. Locals affectionately referred to the train as the “Pommie Doodle,” and looked upon it fondly despite the generally low patronage. The Pennsylvania Railroad had a less affectionate view owing to high operating costs and steep losses. In the last few years of service the Pennsylvania used single gasoline powered cars called Doodlebugs for passenger service to replace the more expensive steam powered trains.

Pomeroy and Newark Railroad schedule from 1913 with connections to Philadelphia. “f” indicates a flag stop, when the train would only stop upon notice to the conductor. These occurred at the smaller stations. (Author’s collection)

The tracks suffered from deferred maintenance and derailments were frequent. It was reported in 1879, less than a decade after construction, “some of the cross-ties are so rotten that the spikes which hold the rails to their places could be drawn out with the hand.”[xxi] Thousands of these rotten ties were removed in 1882. Track crews also struggled with soggy areas that eroded the ties and ballast, including one notorious stretch in New Garden Township a half mile north of Auburn Road. An engineering report singled out this area, “the bottom of the cut becomes so soft in wet weather that a fence rail when stood on end in the ditch will sink down out of sight.”[xxii] Reports of the train running off the tracks due the misalignment of the rails or crumbling bridge supports were frequent. One particularly nasty accident occurred on bridge number 42 at the New Garden and Franklin Township line in January 1904. Chunks of ice rushing down the flooded White Clay Creek damaged the bridge and caused the supports to collapse under the weight of the afternoon train. A reporter for The Avondale Herald provided the dramatic details,

…when the evening passenger train was crossing the heavy timbers gave way at the southern end allowing the front end of the passenger coach and part of the tender to crash through into the roaring waters. The heavy engine was thrown completely over on its right side at the top of the embankment and badly wrecked. The only thing that prevented the passenger coach from falling over completely was that the coupling pin holding it and the combination and milk car at the rear did not break.[xxiii]

P&N Passenger car on Bridge 42 after the accident. Front page of The Avondale Herald January 29, 1904. (Chester County Historical Society Library)

Fortunately, no one was killed. Haphazard repairs were common, but the poor conditions eventually forced the railroad to significantly rebuild many of the 65 bridges on the line. Some of the wooden structures were replaced with steel, and the loose stone abutments were restored with newly invented poured concrete. Many bridges bear the date of their upgrading. Work began on the southern end near Newark in 1910 and reached Avondale in 1911. A few of the abutments on the northern end have 1912 stamps.

Abutment dated 1910 in the White Clay Creek Preserve (2009)

By the 1920’s automobiles and trucks were rapidly cannibalizing the Pomeroy and Newark’s small sources of revenue. Due to waning demand the railroad petitioned to abandon passenger service in the late 1920’s. Despite resistance from residents and business groups the last passenger train rolled down the tracks in September 1928. Freight traffic also dwindled. Business on the sparsely populated 3.5 mile stretch between Landenberg and Thompson, Delaware (just south of the state line) had been scarce for years. The last deliveries for this wooded section meandering along the White Clay Creek were three carloads to Yeatman Station in 1931. The railroad discontinued all remaining through service on this portion of the line in September 1933 and the tracks deteriorated until it was officially abandoned in 1936.[xxiv] Trains continued infrequent service between Newark and Thompson delivering primarily fertilizer and picking up loads of clay until a severe storm on July 5, 1937 heavily damaged the connecting tracks. The Pennsylvania Railroad had no desire or motivation to spend the estimated $25,000 needed for repairs and the Interstate Commerce Commission granted permission to abandon this three-mile section from Thompson to above the industries on the northern edge of Newark in 1938. [xxv]

Freight trains continued to operate on the line between Pomeroy and Avondale three times a week into the early 1940’s. Railcars traveled further south to Landenberg as deliveries or pick-ups necessitated. However, by this time partial carload delivery was outsourced to trucking, and little demand remained south of Avondale for full railcars. In 1942 the line hauled only 23 carloads south of Avondale. Six delivered fertilizer (probably carloads of horse manure for mushroom compost) to New Garden Station, and 17 continued on to Landenberg, including six containing fertilizer, one holding coal, nine with mill products and one containing agricultural products.[xxvi] The revenue from this traffic allocated to the portion of the line south of Chatham was only $36. Simply keeping the track in operating shape cost $4,156.[xxvii]

Sheehan Brothers, the one remaining business in Landenberg that could have provided the line with some traffic, received most of the supplies for their lumber and coal business on the Wilmington and Western Railroad. In the fall of 1942 the Wilmington and Western filed to abandon the end of their line from Southwood to Landenberg. Fearing that this abandonment would force the prolongment of their service to Landenberg, the Pennsylvania Railroad scrambled to petition the Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon their tracks south of Chatham. The railroad cited the dearth of traffic and the importance of the scrap metal from the rails and bridges, valued at $35,000, for the World War II effort. The Sheehan business, now controlled by Wilson & Brosius after Mr. D. Francis Sheehan’s sudden death in September 1942, protested but to no avail. Permission to abandon the tracks was granted in 1943. The Pomeroy and Newark and Wilmington and Western had reached Landenberg together 70 years before, and in less than one year, they were gone.

The Pennsylvania Railroad continued infrequent operation of the 11.5 mile stretch of the Pomeroy and Newark between Pomeroy and Chatham through the 1950’s when additional miles of track were torn up south of Doe Run. Trains off loaded cattle at Doe Run for King Ranch into the 1970’s when the last significant section of the line disappeared. The one-mile stub serving the industries in Newark lingered slightly longer, but it too has vanished.

Today all that remains of the Pomeroy and Newark Railroad are portions of the old track bed, many of the concrete and stone bridge abutments, and a few of the bridges, mainly on the northern portion above Doe Run. Development and farming have erased significant stretches of the grade and even some of the abutments between Doe Run and Avondale. Because of the major grading required, the railroad’s short path through New Garden Township is well preserved. Access to the route is difficult because most of the right-of-way has reverted back to or been sold to property owners adjacent to the line. Fortunately, large sections of the abandoned track bed are accessible south of Landenberg as it twists through the Pennsylvania White Clay Creek Preserve and Delaware’s White Clay Creek State Park. Many of the parks’ trails follow the grade, which is still coated with the cinders spewed from the fireboxes of the Pommie Doodle steam trains. Efforts are underway to use more sections of the line for public paths. The City of Newark is converting the last few miles of the rail bed into a rail trail, and New Garden Township has purchased and hopes to use portions of the line north of Landenberg for trails.

Lifelong New Garden resident, Ben Marsden, graduate of Haverford College, developed an interest in the Pomeroy and Newark Railroad while running on the old rail bed. Grandson of Margaret and Pownall Jones, Marsden shares their curiosity about local history.